I now have good audio for my op. 1, no. 1 Big Waltz (below). It took so long because I was too busy writing my op. 94, a set of pieces for viola or ‘cello. It is traditional to write for one or the other instrument, and then transpose to spread the wealth in another version! I actually wrote two numbers for each instrument. (As I wrote to violist Scott Slapin, who already bestirred himself to release a video of it as the ink was drying on his music stand, “Everyone has to share.”)

It is indeed strange to be blogging now about the work I chose to present first to the greater world, rather than the one I just finished writing. There it is. But I wanted to get the retrospective essay I’ve been working on out there, and this is the perfect medium, to be sure. But I’m planning on relaxing the Series.x/Episode.y format with some of what I’ll call interludes, where I can interject notices about things that wouldn’t fit the current topic. In a sense, these two paragraphs provide a foretaste of what I’m talking about!

So, here goes. Meanwhile, before I was so rudely interrupted.

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

August 2020

I feel as though the best way to afford an overview on my life’s output would be to use the individual sets of program notes I already have as a point of departure, and to annotate those as needed. I had a medical scare last year that leaves me concerned about the abundant loose ends that obtain amid my effects. Although I have largely recovered, I can no longer simply take longevity for granted and want to do well by my compositional charges. Quite a good number of my works have champions among today’s performers, more than I ever dreamed possible for most of my career. And yet, the fact remains that a sizable portion of my œuvre has yet to be performed or recorded at this writing.

Hopefully, this project will help me to get my bearings with regard to the time and energy still available to me. For I must strive to balance the demands my latest works make of me against the responsibilities I feel to find a better place in the world for so many older ones. Sometimes I feel as though I should take my composer’s shingle down entirely, and just become my younger self’s amanuensis. The stern muses I interact with would seem to have quite different plans, however!

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

In the late 90s, as my confidence with and expertise in music processing evolved, I decided to “start over,” to go back to works in yellowing manuscripts from my college days and finally make this juvenilia available to share. Most of the works that began the series of opus numbers I am still using arose in response to specific academic assignments. But others I rather assigned to myself, either out of inspiration or from a desire to develop certain techniques for the toolbox that I continue to access on a daily basis. Once the computer engraving of opera 1 to 3 was complete, I wrote the following general introduction, which I planned to include with each opus in turn. Then I would complement it with notes specific to the given opus. Ultimately, however, I abandoned an enveloping format along such lines in favor of the three independent essays which appear further below. I feel that the rejected introductory précis does have a proper place here, though, yielding as it amply does both background information and foreground context. The italics are original. (Pardon the idealization of my decades of high school teaching wherewith it opens. Many would probably contend that it interfered with the arc of the artist’s career I might otherwise have enjoyed!)

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

I was late in coming to music as an avocation, let alone as a calling in life. One could say that in my present teaching activities I am attempting to provide opportunities for youngsters to explore creative realms that were mostly closed to me in my own upbringing. I led a comfortable, middle-class existence as a child; it was simply that music did not figure significantly in the picture either at home or in school.

In college I finally learned the rudiments of musical art, and it was not long before I began to try my hand at composition. In the fall of 1976 I used some piano pieces I had written earlier that year as grist for the orchestration mill run by my teacher Al Reed. (There was a poorly kept secret that Professor Reed had so many band pieces in print that he had to resort to pseudonyms for all but his most signal achievements!) In the first meeting of our class he said that the instrumentator must enter into the creative shoes of the composer of the original music, and then, as Britten said, think through the instruments. I balked at the prospect of thus involving myself in the creative matrix of great composers (whose works Reed proposed to assign as exercises), and approached him about using my own piano works instead. He looked at these and consented. “Recompose” was Stravinsky’s term for this process, and it was a relatively easy matter for me to invoke again that compositional influx I had, in point of fact, left so very recently. (Whereas Stravinsky often waited decades to orchestrate his own piano works.)

The fruits of these efforts were three suites: op. 1 for full orchestra, op. 2 for concert band, and op. 3 for strings. I learned all too soon that no-one at the time was eager to put such less-than-groundbreaking works on public display. (And from the pen of a piano major at that! I should mention for the record that, along the now twenty years intervening, a few stalwart conductors have seen fit to indulge me so.) The pity was this: that I was no longer content to play any but a handful of these works on the piano for which they had originally been written. Most of them had come to seem impossibly dry and manqué absent the countermelodies and various special effects I devised for them later. Like most composers, I tend to put most of my energies into promoting my most recent work. (When six years later I finally met a conductor who took an active interest in my music, I composed a new orchestral suite for him, my op. 39. Through him I met a band director who was soon to ask for something too. However, instead of proffering the anodyne rag wherewith op. 2 opens, I wrote quite the newfangled one for him, my op. 49!) After years of experiencing a dream about rediscovering a lost piano piece, I finally got the recurrent message from my Dreamshaper that these early works needed to be acknowledged and made available, and so now I am at last… (finally) using the computer technology that has since evolved… (Finale) to prepare them for promulgation. The world can embrace these twelve numbers, as I now do, or reject them, but at least they are there for the sampling.

October 2020

Regarding that “handful” of piano originals I did not abandon: these were eventually subsumed, along with later works, into a set of piano Impromptus, my op. 14. (I will address said compendium once we get that far!) For the record, the only strain in all of opus 1 (full orchestra) that I continued to play on the piano was the bittersweet one from flute and obbligato clarinet, heard in the middle of the Big Waltz opener. The Galopade from op. 2 (concert band) is redoubtably souped-up from the modest piano original wherewith the op. 14 Impromptus open. Au contraire, the Valses nobles from op. 3 (string orchestra) track much more closely to the piano original Biscayne Bay Waltz heard in the op. 14 catch-all.

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

An aside now, before the individual program notes I conjured for the three breakout opuses I had neglected so long. When works of mine get programmed, I am often asked to shorten the program notes I submit. In fact, these days I sometimes from the get-go add in, unprompted, an alternative shortened version! It seems then that I always took an archival approach to my various verbal jottings. Invariably would the question arise: who exactly is it you are addressing? I do recall making the distinction early on between what I might want to say to a prospective performer, whom I would expect to be delving deeply into the composition itself, as opposed to the average audience member speed reading (quick, before the lights go dim!) from the program someone handed to him. So, we get in effect comprehensive notes for the former; pruned ones for the latter. I will give both here when alternative versions obtain, between which the reader can choose.

Op. 1 is a Divertimento with four numbers, for double-woodwind orchestra. I would later write two more divertimenti (opp. 39 and 61) and, oddly enough, confine them to exactly the same orchestra as that I was assigned here to use, away back in my novice days!

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

Divertimento I for orchestra, op. 1

Orchestrations (1976–77) of my own piano originals (1975–76). In response to college assignments, except for the opening Big Waltz, whose inclusion I thought would make for a satisfying set.

1. Big Waltz

I was always amused by the use of this term by teachers whom I was accompanying in ballet classes as these themes were emerging. Was it meant to convey the need to propel the dancers across the floor, in a highly rhythmic waltz counted in one or a fast three? Or was it simply a brusque translation of “Grande Valse,” brillante or otherwise? (Big, bright waltz?) Although the raw materials for this number were first improvised in eight-bar strains during ballet classes (like my later dance album for piano, op. 63), in the working out for the orchestra (or should I say, working up for the orchestra?) quite a bit of irregularity set in, in an introduction, interludes, developments, and finally a coda based on the intro (which had itself derived from the first, balletic strain).

2. Ländler

The next two numbers here were successive in the piano recueil in which they first appeared as well. It was my composer friend Charles Porter, dedicatee of the op. 3 Bagatelles for strings (of similarly academic provenance), who first pointed out to me that each begins with the same two upbeat notes, spelled differently because of their respective keys, but sounding identical to the listener (particularly given their common tactus). I decided, when doing the orchestration, to make great dramatic capital out of this simple coincidence, using a stock-in-trade diminished chord to pivot, first back to the opening key for the repeat of the Ländler, then forward to the key of the Lullaby as it approaches. A certain rustic ponderousness characterizes the Alpine Ländler generally, accounting for some rather thick orchestration in the present specimen, particularly from the hobnail-booted percussion. (I actually count twelve real voices at one point, amid reichlich doubling!)

3. Lullaby

Follows the preceding without a pause. The triplets in the violas provide momentum without mitigating the serenity of the completely diatonic melody passing between violins and solo brass. The use of just single winds at the end, and moreover the dropping out of that triplet counterrhythm, move us from serenity to somnolence itself.

4. Holiday Rag

After a short intro in the strings, the lower brass usher in each phrase of the principal strain with a dry, five-note scale. In keeping with Joplinesque tradition, the repeat of the rag’s second strain is more elaborate than the first time through. But solo flute breaks out of Joplin’s mould, interrupting said repeat with a show-off cadenza! We hear the indignant lower brass attempt to push things along. They sit poised to play their little scale figure to herald the recap of the opening strain, which tradition leads us to expect. After this strain is finally recapped, there’s time left for but one more strain (whereas Joplin, at this juncture, would typically feature two additional formal sections). When the first horn seeks now to develop material out of this concluding strain, it gets unceremoniously swept aside by the full orchestra, which clearly has lost patience with all such fussy goings-on!

I was actually not the first person to orchestrate a piano piece of mine. I got the idea from my friend Kenneth Uy, who had orchestrated a very early piece (since withdrawn, unfortunately) while we were still undergraduates at Columbia. (He was a music major, of course, but I was still racking up credits in chemistry at the time!) I had dedicated the original (piano) version of “Holiday Rag” to him, so it was only natural that the orchestral suite subsuming the number also get inscribed to this extraordinary musician and supportive friend.

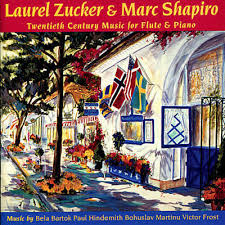

Victor Frost

27 I 96

New York City

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

[Condensed version of same follows.]

Divertimento I for orchestra, op. 1

1. Big Waltz

I was always amused by the use of this term by teachers whom I was accompanying in ballet classes as these themes were emerging. Was it meant to convey the need to propel the dancers across the floor, in a highly rhythmic waltz counted in one or a fast three? Or was it simply a brusque translation of “Grande Valse,” brillante or otherwise? (Big, bright waltz?)

2. Ländler

A rustic Alpine dance. The often heavy orchestration reflects the dancers being hobbled by their hobnail boots! The Lullaby upcoming, although unrelated in either key or time signature, begins with the same two upbeat notes as the Ländler; I chose to arrange the numbers into a dovetailed whole.

3. Lullaby

Follows without a pause. The triplets in the violas provide momentum without mitigating the serenity of the completely diatonic melody passing between violins and solo brass. The use of just single winds at the end, and moreover the dropping out of that triplet counterrhythm, move us from serenity to somnolence itself.

4. Holiday Rag

The repeat of the second strain of this rag is more elaborate than its initial statement, in keeping with Joplinesque tradition. Very un-Joplin-like, though, is the repeat’s interruption by the flute, which engages in a show-off cadenza. This considerably delays the recap of the rag’s opening strain tradition leads us to expect. Owing to the time lost, there follows but a single strain, another departure from tradition. When solo horn now attempts to develop this new material, it gets unceremoniously swept aside by the full orchestra, which has clearly lost patience with all such fussy goings-on!

My friend Kenneth Uy was actually the first person to orchestrate a piano piece of mine, while we were still undergraduates at Columbia. (He was a music major, of course, but I was still racking up credits in chemistry at the time!) My having dedicated the piano original of “Holiday Rag” to him, it was only natural that I inscribe this orchestral suite subsuming said number to him.

Victor Frost

28 I 96

New York City

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

While others in my orchestration class were figuring out what the lowest note on the oboe was, Al Reed’s biggest complaint to me was that I was too intent on adding to, or even essentially rewriting my piano morceaux. The main tune to the piano original of Big Waltz was 32 measures that fit on a single page. As an exercise in self-restraint I was to pretend it was the work of another composer, one which I was not at all free to elaborate. All my other exercises got A’s or A+’s. This got a B. But that summer in a kind of, so to speak, creative slingshot effect, I produced the fulfillingly footloose, free-form version you can hear below. (It transmogrified, in fact, into by far the most elaborate of the twelve numbers in opp. 1 to 3.) I feel it now deserves at least a B+, perhaps even an A- if you’re in an indulgent frame of mind!